Family growth, deconversions and housing supply in North Center

What we can learn from Chicago's hottest neighborhood for families

Last November, I wrote about the surprising fact that the population of Chicago’s Logan Square neighborhood has declined over the past 20 years. As the neighborhood had gentrified, with huge increases in average incomes and a sharp rise in college-educated and white residents since 2000, the population had simultaneously fallen.

But if Logan Square had been unexpectedly shrinking, the North Center community area — a hotspot for families tucked along the Brown Line, with an average household income of $148,600 — stands out in the opposite way.

In Logan Square and neighboring community areas on the Northwest side, a decreasing number of families has driven population loss. As housing became more expensive and families left, household sizes fell accordingly. On the other hand, North Center has experienced a surge in its population of children — in fact, from 2010 to 2020, it saw the most rapid growth in the under-18 population among all Chicago neighborhoods.

More surprisingly, during this period North Center saw a net decrease in the number of housing units. From 2010 to 2020, North Center was the only core-city neighborhood to experience population growth along with a decline in the number of housing units — exactly the opposite of Logan Square.

Though the two neighborhoods have experienced opposite trends in their household sizes and population growth, taken together they demonstrate related ways that gentrification and a rising ability to pay for housing can manifest in a neighborhood. They also offer an important lesson for the future growth of populated urban areas, and the role that our policy choices play in shaping the growth of already-populated neighborhoods.

What’s changing in North Center?

It’s unusual to see a neighborhood’s population grow without adding more housing units to accommodate those people. How could this be happening?

One reason is that an increasing share of the housing stock is in single-family homes with more bedrooms. North Center seems to be one of the few neighborhoods in Chicago where we can clearly point to housing deconversions — i.e. when small-scale multifamily housing is renovated into a single-family house — as a key factor reshaping the neighborhood. Research from the Depaul Institute for Housing Studies, which tracked deconversions from 2013 to 2019, showed that North Center, Lake View, and Lincoln Park were by far the neighborhoods losing the greatest share of 2-4 unit buildings to deconversions.

American Community Survey data from 2010 to 2020 reflects this change, showing a loss of over 1,000 units in 2-4 unit buildings within North Center, alongside a similarly precipitous rise in 1-unit buildings (see equivalent figures for Lake View and Lincoln Park at the bottom of this post).

It’s no coincidence that Chicago’s most deconverted neighborhood is also one of its wealthiest. Today’s residents of North Center have far more purchasing power and higher living standards than the families that bought their new 2-flats a century ago. Although deconversions might have negative downstream impacts on the neighborhood’s housing market, it shouldn’t be shocking that these households would be willing and able to pay a premium for more space and a yard to themselves.

Equally striking from the data above, however, is that there is no difference in the number of housing units in larger buildings. While deconversions have reshaped one segment of the housing market, another segment of the housing market hasn’t changed at all, even though the neighborhood is clearly in demand (more to say on this later).

Given the simultaneous occurrence of significant housing deconversions and rapid growth in the under-18 population, a natural hypothesis is that the increase in North Center’s single-family homes has helped to enable the neighborhood’s boom in families.

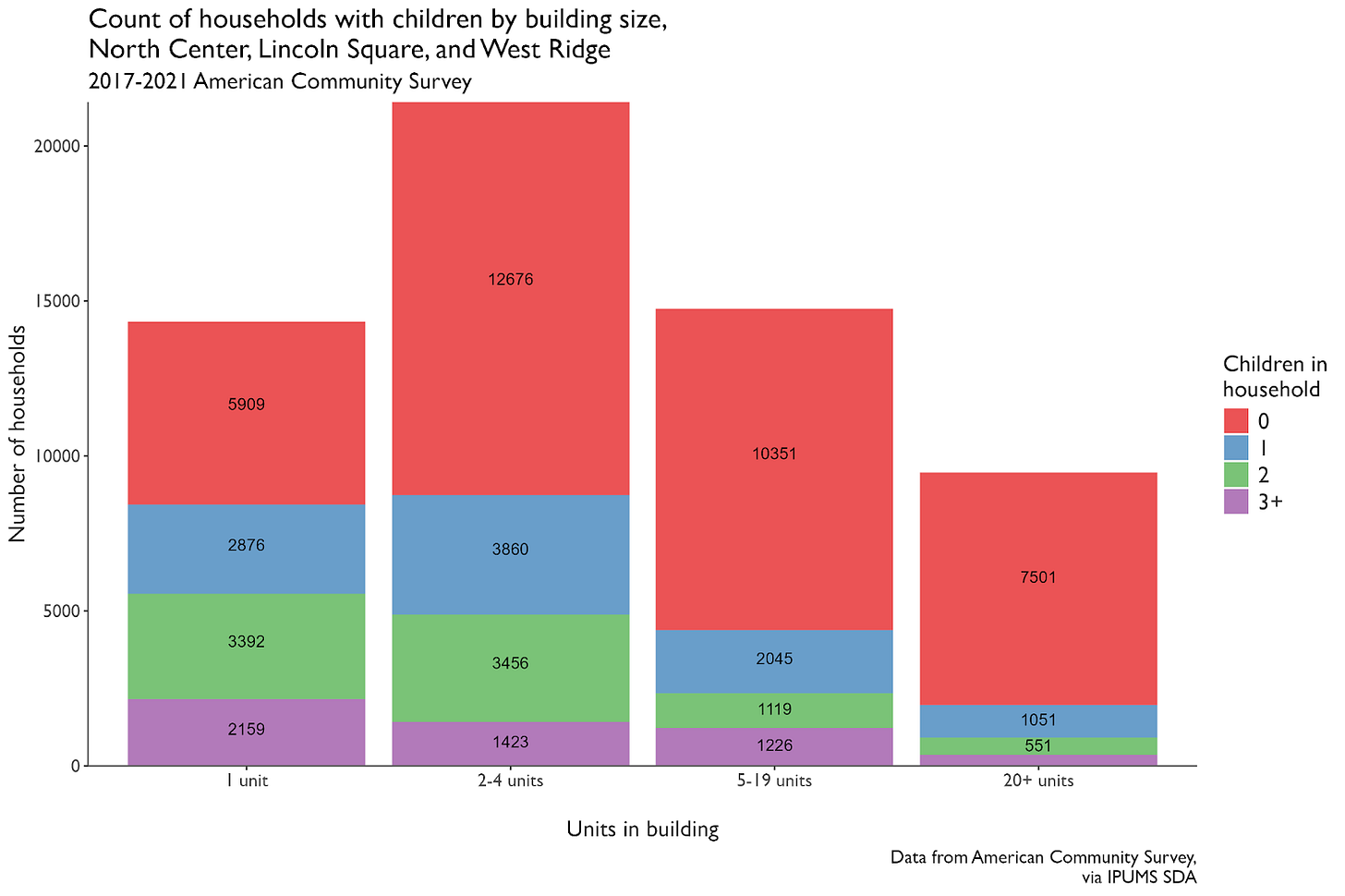

One suggestive statistic supporting this theory comes from ACS data, showing how common families are across different sizes of buildings (because this data comes from IPUMS, it has to be aggregated to a slightly larger geographic level that also includes Lincoln Square and West Ridge1. See map).

Single-family homes are the only size of housing in which the majority of households have children, and children become less common as the number of units in a building increases. This doesn’t necessarily show that North Center’s deconversions have driven the neighborhood’s family growth, but it does show that families generally select strongly into single-family homes, and it helps explain why both families and housing deconversions have recently proliferated in North Center.

With its relative prominence of housing deconversions — which seem to have actually driven down the number of housing units in the neighborhood — North Center looks fairly unique. At the same time, however, North Center’s demographic changes might also demonstrate something more generally informative about gentrification and neighborhood change.

The “U-shaped curve of gentrification”

With its growing number of families and shrinking housing stock, North Center is experiencing opposite trends as Logan Square. But it might not exactly be correct to conceptualize the two neighborhoods as opposites. Perhaps they’re both at different points along the same progression.

Chicago housing expert Daniel Kay Hertz has proposed the concept of a “U-shaped household curve” during successive waves of gentrification. In a highly stylized form, the theory goes as such: in early waves of gentrification, childless households with relatively higher incomes outbid existing families for housing. These smaller households create the downward part of the U-curve. But once a neighborhood has become wealthy and amenity-rich, families with even higher incomes start to move into that neighborhood and replace those childless young professionals. Household sizes begin to rise again.

As one snapshot, take a look at the populations of children in North Center and some of its neighboring North side CCAs.

Like North Center, Lake View and Lincoln Park have also seen strong growth in the population of children. According to data from CMAP, median household incomes in all three CCAs were above $100,000 in 2020. These three neighborhoods look to be on the back end of the curve, with high-income families flocking to them.

On the other hand, in Uptown — median household income of $66,900 in 2020 — the population of children has fallen precipitously. Indeed, Uptown’s decline in children makes it look a lot like Logan Square or Avondale, which had comparable incomes in 2010. With income (moderately) rising through the 2010s and families leaving, Uptown is on the front end of the curve.

Finally, Lincoln Square seems to have just passed the bottom point of the curve: its population of children fell from 2000 to 2010, but in the next decade it grew slightly. At $90,600, the 2020 median household income in Lincoln Square is between Uptown and the wealthier North Side neighborhoods. In this respect, Lincoln Square looks more like the West Town CCA (which includes Wicker Park and Bucktown), where a large decline in children has slowed down as the neighborhood has become fairly rich.

These neighborhoods are all seeing their incomes rise, but that demand growth manifests in different ways depending on how far a neighborhood is along the cycle of gentrification.

Certainly, this is an imperfect theory. Neighborhood-specific amenities beyond income and housing costs also play major roles in where families choose to locate — schools, parks, stores, and so forth. But as a high-level depiction of household changes during the gentrification cycle, it seems to capture some important trends.

Change is (partially) a policy choice

We can’t easily change the household dynamics of the U-shaped gentrification curve, although it’s not clear why we’d want to anyways — for example, how can you stop an early-stage gentrifying neighborhood from becoming popular among younger childless households? And is there a reason to stop high-income families from moving into neighborhoods towards the end of the gentrification curve?

While we needn’t seek to stop households from growing or shrinking, we could do far better to accommodate more people in the neighborhoods they’d like to live in, which will also reduce (though surely not eliminate) displacement pressures for incumbent residents.

No matter what point a neighborhood is along the gentrification cycle, it almost certainly needs to expand its housing supply. When residents’ incomes rise, they’ll seek to consume more housing for themselves, and without new housing getting built, all of that increase in housing demand is absorbed solely by the existing units. That scenario isn’t going to benefit less wealthy residents.

It’s a reasonable move to restrict deconversions as has been done on the Northwest Side, where there is now a substantial fee for demolition of 2-4 unit apartment buildings. Deconversions are widely derided in Chicago housing discussions, and that’s mostly fair — they reduce the housing supply and raise the price of housing (although, as in North Center, they clearly provide some direct benefit to those who move into them).

But we shouldn’t over-focus on deconversions as a housing affordability issue. Isn’t it just as much of a problem that from 2010 to 2020, North Center saw no increase whatsoever in larger apartment buildings? If deconversions are bad because they reduce the housing stock, a dearth of new construction does exactly the same thing. Two larger apartment buildings recently approved in North Center will add 200 new units of housing, or as much housing as is lost in 100 three-flat deconversions. Places like North Center need to allow a lot more buildings like these.

As housing researcher Yonah Freemark recently wrote, the downtown and downtown-adjacent neighborhoods are the only places in Chicago that have meaningfully expanded their housing supply in the last 20 years. But in much of the North and Northwest sides, high housing values clearly indicate substantial unmet demand to live in those neighborhoods. The land use rules in these areas are clearly problematic:

“On the Northwest Side, most land is zoned to allow only one- or two-family homes to be built. And on the North Side, just 2 percent of land allows construction of high-density multifamily buildings. These are high-opportunity neighborhoods, where schools boast higher test scores and where grocery stores are easier to come by. But the city’s zoning choices may prevent these communities from accommodating a greater diversity of residents.”2

As we seek to add much-needed density to places like North Center, we should also ask what the neighborhood’s child boom can teach us about supporting children in urban areas. Although one component of North Center’s recent family growth may have been an increasing supply of single-family homes, this doesn’t offer a very sustainable path for further supporting families in cities.

To keep cities both vibrant and affordable, it will be necessary to figure out how we can support families in denser housing typologies, which we are currently failing to do. That’s a big and difficult question, and within the scope of this blog post I can’t offer much in the way of solutions. But looking at North Center’s recent changes do suggest some unresolved tensions in our current formula for family-friendly urbanism.

The most immediate lesson to draw, however, is that Chicago’s most popular neighborhoods for families need to be working harder to build more housing. It shouldn’t be the case that the neighborhood with the fastest growth in children also saw its housing supply decrease in the last 10 years. Deconversions are a problem for North Center and other nearby neighborhoods, but a bigger problem is that these places will remain out of reach for most Chicagoans if they can’t expand and create more places for people to live.

Appendix: Two bonus figures

It’s PUMA 3503 in 2010, for all you microdata fans out there.

Freemark’s third category of Chicago neighborhoods are disinvested areas on the South and West sides that build very little housing, even though the zoning allows for considerably more density.

Huge fan of your writing. Thank you for bringing real data into the conversation and for resisting tropes in order to arrive at interesting and nuanced conclusions!

Here’s my idea on how Chicago can allow single-detached houses at the same scale and density as two-flats: cottage courts.

https://www.stevencanplan.com/2022/08/allowing-cottage-courts-in-chicago-requires-changing-the-zoning-code/