What do we mean when we say "filtering?"

Distinguishing between two different housing market dynamics

“Filtering” is a very important process to understand when thinking about how housing markets operate across time and space — and particularly in thinking about urban housing affordability. It also ties very closely to contemporary debates surrounding housing supply. For example, when local governments consider whether to allow a new luxury apartment building to be built, how should they expect it to affect citywide access to housing supply? Likewise, for a larger-scale upzoning: if a big zoning reform enables a boom in housing construction, how will that affect the housing market? Thinking about filtering helps us answer these questions.

Still, in housing policy discussions there seems to be frequent confusion about what “filtering” actually means. This is an understandable confusion, because filtering is commonly used to describe two related but distinct processes.

“Within-unit” filtering, which describes how the price of any given housing unit changes over time. In other words: how does today’s luxury housing become tomorrow’s moderate and low-cost housing?

“Across-market” filtering, which describes how newly developed housing creates vacancies in cheaper housing throughout a housing market (defined across an entire metropolitan area). In other words: how does today’s luxury housing affect today’s already existing moderate and low-income housing?

Both of these are important dynamics that are well-documented empirically, but in discussions around new housing development the two are often confused. Both of these processes matter, but they occur at different time scales and have different implications for how new housing relates to housing affordability.

In this blog post, I’ll seek to clarify these distinctions, take a look at what the economics literature has to say about each type of process, and discuss why these ideas matter for active policy debates.

Within-unit filtering

Over time, we might expect a housing unit to get cheaper. Housing is a physical object that deteriorates over time, leading to lower quality and higher maintenance costs. Thus, we would generally expect that residents of older housing will have lower incomes, even if that housing used to have richer inhabitants. This is “within-unit filtering”.

This has been the subject of plenty of research, including an influential paper on the subject published by Stuart Rosenthal in 2014. By tracking resident’s incomes in the same housing units over time, Rosenthal showed how housing tends to meaningfully filter downwards across the United States.

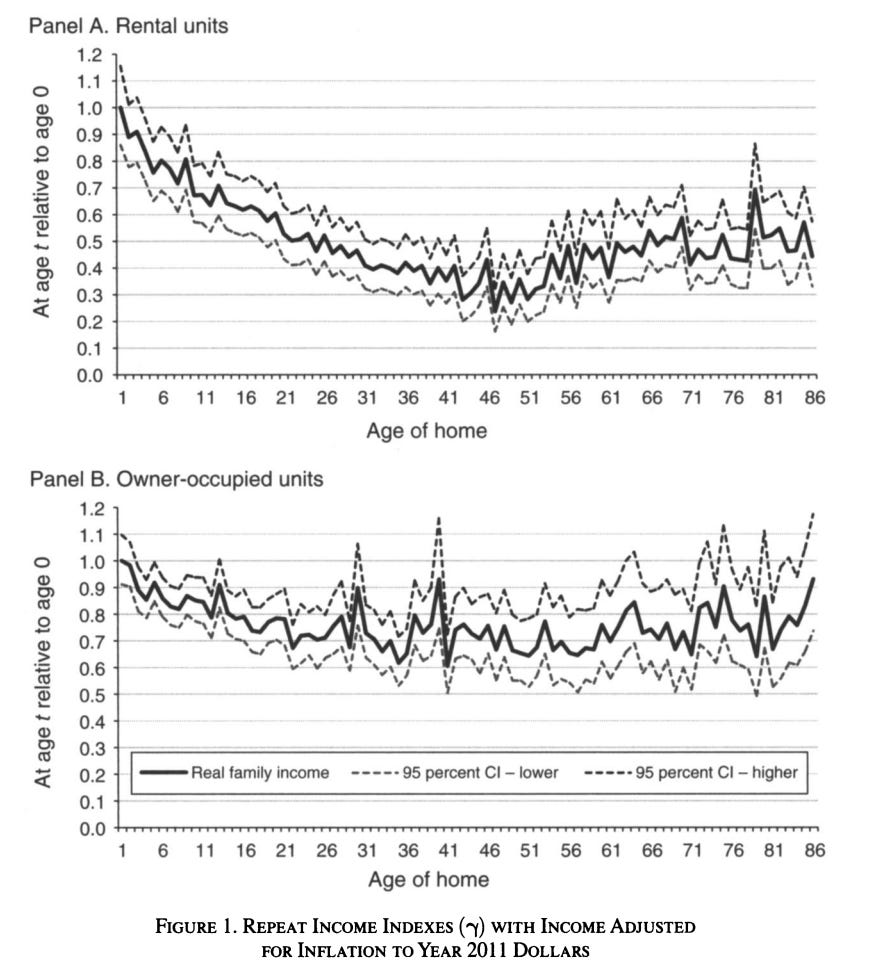

Rosenthal’s figure below shows how the incomes of housing occupants decline over time for a given housing unit. Within two or three decades after housing is built, residents with considerably lower incomes can afford to move in. For rental housing, residents eventually have incomes less than half of the original residents’ income, while filtering happens about half as much for owner-occupied housing.

However, rates of within-unit filtering are not fixed, as conditions in an urban area’s housing market can drive substantial variation in the filtering process. More recent research has examined this variation.

This figure, from a 2022 paper by Liu et. al, is similar to the one above, but it separately examines a sample of metropolitan areas. This demonstrates how much filtering can vary city-to-city. In Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles, filtering has actually happened in reverse, with housing being inhabited by increasingly wealthy residents as it ages.

Why does filtering sometimes fail to occur, or even work in reverse? This is an indicator of substantial housing market problems for a city. Ideally, it shouldn’t be the case that the residents of a housing unit — which in a physical sense, typically only becomes lower-quality as it ages — are becoming richer and richer over time. This happens when housing prices are growing quickly, and demand for housing is outpacing supply.

In fact, Liu et. al’s paper shows that downward filtering of housing happens more quickly in metropolitan areas with more elastic housing supply, meaning that the supply of housing can grow more in response to increasing demand. They even show that the rate of downward filtering has a negative correlation with a city’s strictness of land use regulations — if a place has more stringent zoning and land use rules, it tends to have worse rates of filtering.1

In sum, this research tells us that within-unit filtering certainly can happen, but market and policy conditions determine whether this mechanism can viably create low-cost housing. If a city is failing to keep housing costs affordable, then housing is probably not filtering downward (and vice versa). When a new unit does eventually filter down to lower-income residents, it can take decades.

However, for all the attention paid to within-unit filtering, it doesn’t seem like the most important type of “filtering” to think about with regards to housing affordability. Why should we be primarily concerned with the affordability of any specific housing unit? Affordability matters much much more at larger scales — at the very least, at a neighborhood level, but also throughout an entire metropolitan area.

Across-market filtering

This larger, metropolitan-level scale is where “across-market filtering” happens. When new housing units are built, new residents move in and vacate their previous units. Often, these residents leave behind cheaper housing, creating another opportunity for someone to move, and so on. This process can continue down the spectrum of different housing cost levels.

Economists refer to these as “migration chains,” as one person’s migration into a new housing unit creates a chain of moves across an urban housing market.

In the past few years, access to detailed data on individuals’ addresses has greatly increased our understanding of this market-wide filtering. Researchers can now track how individuals move over time, documenting how residents move across different kinds of housing and neighborhoods after new housing is built. In particular, two papers have demonstrated that migration chains are a high-impact mechanism by which new housing development can increase the availability of lower-cost housing.

The below map of Chicago, from Evan Mast’s 2023 paper, helps visualize this phenomenon. New market-rate developments are heavily concentrated in the high-income core of Chicago. The resulting migration chains primarily create new vacancies close to the new buildings, but they also open up housing units across a broader range of neighborhoods (the Minneapolis Fed also has a nice interactive depicting this dynamic in Minneapolis). Keep in mind that this figure only depicts the first wave of the migration chain — all those secondary vacancies will lead to some tertiary vacancies, which are likely to be further geographically distributed.

Another key figure from Mast’s paper estimates the “equivalent housing units” created in lower-income neighborhoods as a result of new development in a high-income neighborhood. In other words, this is the average number of vacancies that a new building generates in different neighborhoods, including neighborhoods with lower incomes or lower shares of white residents. This figure shows that a new market rate housing unit leads to about 0.7 newly vacated units in below-median income neighborhoods, and smaller but still-meaningful amounts of housing in further disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Additional research on migration chains from Bratu et. al confirms that filtering directly benefits low-income individuals. Because they have more detailed socioeconomic data, they confirm that many of the actual individuals participating in migration chains have below-median incomes (although their data is from Helsinki, where lower income inequality suggests that migration chains will be more connected across income levels than in the United States).

Compared to within-unit filtering, migration chains can lead to much quicker impacts from new and expensive housing. For example, both of these filtering papers show that essentially all of the across-market filtering from new buildings happens within two to five years. This helps explain why other recent research shows that new housing units lead to lower rents within just one year.

You might observe that these metropolitan-scale migration chains are one of the key mechanisms that enable within-unit filtering. Yesterday’s luxury housing can become tomorrow’s affordable housing, but this requires new housing to be built today, sparking migration chains across the income spectrum.

In conclusion

While it will typically take decades for a new housing unit to become affordable for lower-income residents — and in some circumstances, this might never happen — this isn’t the most relevant metric to look at when thinking about how new housing impacts housing affordability. Across-market filtering, via migration chains, is more important. Furthermore, research shows that across-market filtering can benefit low-income participants in the housing market quite quickly.

As I often note when writing about housing markets, market-driven affordability has meaningful limitations. Any economist would agree that there is some point at which rents cannot fall any further — after all, buildings still cost money to maintain, and rents need to cover those costs. At this point, we need to provide public subsidies that can close the remaining gap.

But the size of that remaining gap has a lot to do with whether places are willing to build new housing, relieving pressure across an urban housing market.

Downward filtering of housing also happens less in cities with faster income growth, or faster population growth. And at a local level, gentrifying neighborhoods see more upward filtering.

Great post! I thought Yoni Appelbaum's description in "Stuck" of "moving day" was a brilliant example of across-market filtering.

Super neat.

Chicago presents itself as a city defined by neighborhoods and defended by each neighborhoods alderperson. Arguing for an up zone to develop market rate units is a neighborhood issue and a common hurdle for development.

How does the across market filtering affect the neighborhood the units are being delivered in vs the city itself? On what time scale?